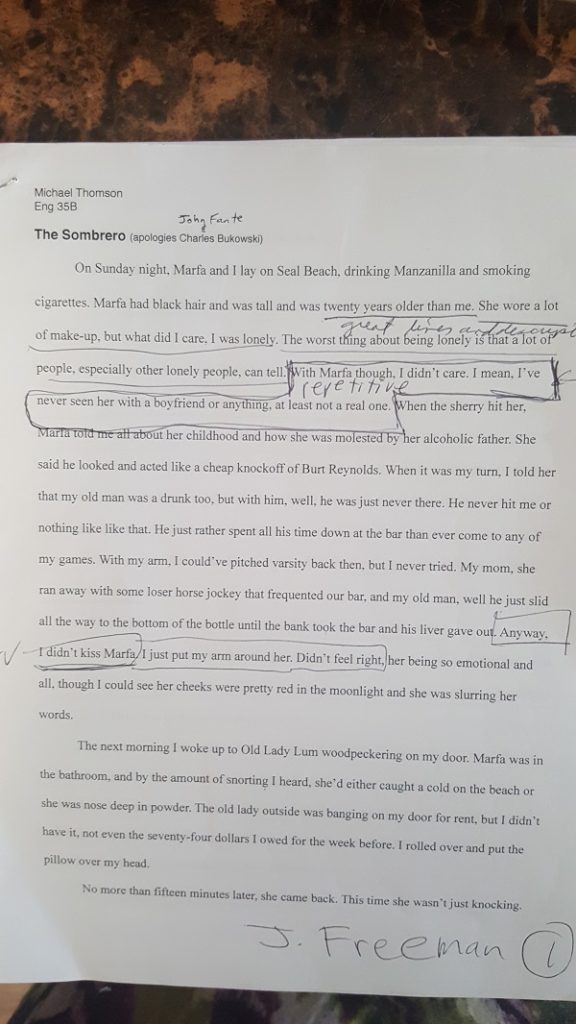

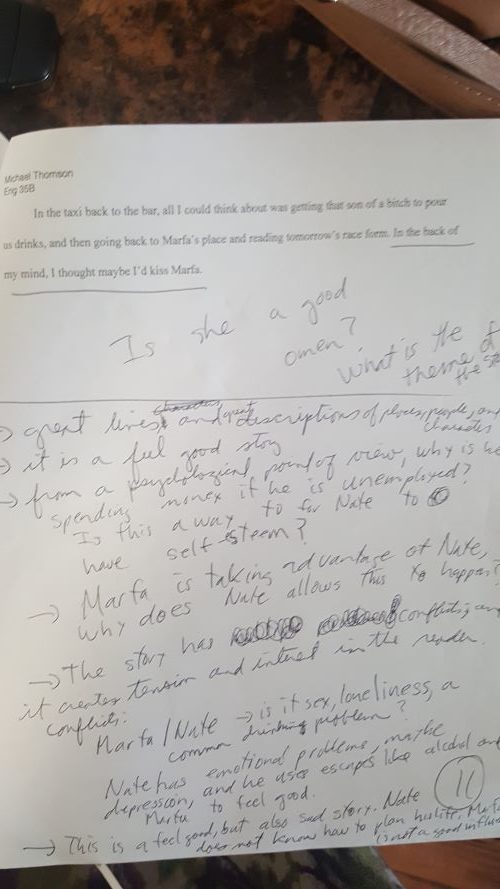

After Mike’s funeral, when we were packing up the apartment in Rancho Cucamonga, I found a stapled copy of a story Mike had written in a box of his class notes and other writing from over the years. ‘The Sombrero’ had Mike’s name and “Eng 35B” at the top. It was eleven pages long and covered in handwritten notes from a classmate.

In a writing workshop, you hand out copies of your story to everyone in the class, and each person critiques it. It can be a very stressful and demoralizing exercise, but it’s a way to get a lot of feedback on your writing all at once so you can decide how to go back and edit it, rewrite it, or scrap it.

I never knew this story existed, but that didn’t surprise me. It always took a lot of convincing to get Mike to show me any of his writing. He never thought it was very good, and nothing I said or did seemed to convince him otherwise. I mean, he was accepted into Columbia’s MFA writing program — they don’t admit just anyone.

The first time he finally showed me something he had written — his story, ‘The Train’ (which will be published in the upcoming Voices for the Cure anthology) — I went nuts over it. I begged him to keep writing. Even long after we broke up that first time, every time I saw him.

Now that he’s gone, everything he touched is like gold, like a priceless relic. I took a picture of each page of The Sombrero with my phone and put it back in the box for Sheila. The next day, heartbroken, she fled town, driving up the 101 to Santa Cruz with her dog Bodhi and Mike’s ashes in an urn made of wood.

I totally understood. Those early days were such a blur of numbness and pain.

I finished packing up, said goodbye to Renee, and drove the van back up north to Oakland.

After I settled back in at home, I gathered up other stories Mike had written over the years, stored on thumb drives, and got to work. I had asked him if he’d like me to to try and get some of his stories published, and he said sure.

He’d been working on a novel — about a young man in San Francisco who becomes a trucker — for years, but never finished. I found several incomplete pieces of the story, different versions of the plot, and they’re very good. I’m still trying to figure out if I can piece them together into a short story, if not a novella. But I want to keep it intact, all him.

John Fante

It’s clear that Mike shared ‘The Sombrero’ in a fiction-writing workshop, but I’m not sure if it was at Columbia or during his time at City College of San Francisco (where he also helped run the college literary magazine, Forum).

But when I saw on this hard copy that he’d included the parenthetical note, “apologies to John Fante & Charles Bukowski,” with Fante’s name written in by hand like an afterthought, something clicked in my mind and I remembered something he had told me years back.

In one of the workshops he had attended, he’d told me, during a class critique of one of his stories, a fellow student had made a snotty remark that Mike was imitating John Fante’s writing voice. He was stunned.

There was just one problem with her accusation: At that point, Mike had never even heard of Fante.

But he sure as hell started reading Fante after that. He liked it. He did sound like Fante, he realized, but how could he have imitated an author he’d never even read? It didn’t mean he was stealing someone else’s voice, as the classmate had implied. It didn’t mean that he had no sense of his own voice. It meant that he and Fante had been surfing the same cosmic wavelength all along.

Turns out Bukowski was influenced by Fante. Turns out it’s perfectly acceptable if your writer’s voice resembles another writer’s voice, or several other voices. As a writer, as an artist of any kind, you stand on the shoulders of those who came before you. As you read and discover books and music and art and life, you absorb different flavors, then you take everything you’ve experienced and turn it all into a whole new flavor, one that has undertones of this and that but that’s your own.

Then, with any luck, the next person hears your voice and likes it, absorbs some of your ‘flavor’ into their own work, and it continues. Many artists expect or even hope that you’ll do this. They help make you who you are, and you make it your own. That’s how art works. That’s the magic of it.

So what at the time had been a hurtful comment turned into a source of inspiration. I love that he included that “apologies to” note with this story. I take that to mean that he not only admitted to but was proud of the influences that helped make him who he was a writer.

I don’t know if this was the story that had prompted the Fante remark, but it may very well be.

Messages

Over the months, when I miss him so much I don’t know what to do with myself, I return to his stories. It sounds cheesy, but when I’m editing, deep in his writing, I feel like he’s communicating with me. It’s like listening to music that offers secret messages in the quiet spaces between the notes.

In his stories, I hear his voice between the lines. I recognize in his characters some of his own most endearing traits, some of the deep feelings that he must have struggled with. The subtle quirks he noticed in others. The ways he might have tried to comfort himself when he was lonely.

The other night, empty and overwhelmed by sadness, I returned to The Sombrero. As I sat in my living room at sunset, I finished transcribing the story from the 11 photos I’d saved to my laptop, then gave it a very light edit. I looked up to see that the room was dark, but I didn’t bother to get up to turn on a light.

In the story, Mike mentions a Patsy Cline song, so I googled it to be sure I had the complete title. Before I knew it, YouTube was feeding one sad Patsy song after another into the darkness around me as I worked in the glow of the screen.

The Sombrero

By Michael Thomson (apologies to John Fante & Charles Bukowski)

On Sunday night, Marfa and I lay on Seal Beach, drinking manzanilla and smoking cigarettes. Marfa had black hair and was tall and was twenty years older than me. She wore a lot of makeup, but what did I care. I was lonely. … Read the complete story.